Barcelona is full of Gaudí buildings that feel almost otherworldly — the swirling stone of Casa Batlló, the sculpted waves of La Pedrera, the impossible geometry of the Sagrada Família. But before all of that, before the fame and the crowds and the architectural audacity, there was Casa Vicens. This was Gaudí’s first house, the place where a young architect still in his twenties began to test the ideas that would eventually define him.

Built between 1883 and 1885 as a summer residence for Manuel Vicens, a stockbroker with a taste for the exotic, the house sits quietly in the Gràcia district. From the outside, it’s a riot of patterned tiles, brickwork, iron balconies, and Moorish influences – a kind of architectural collage that must have startled the neighbours when it first appeared. It’s unmistakably Gaudí, but also not quite the Gaudí we think we know.

And that, I think, is part of its charm. Casa Vicens doesn’t feel as polished or as modern as his later houses. It has the energy of a debut – bold, experimental, occasionally eccentric, full of ideas that haven’t yet settled into the confident, fluid language of his mature work. If Casa Batlló is a symphony, Casa Vicens is the first rehearsal where you can hear the themes beginning to form.

What I love about it is that it feels like opening a sketchbook. You can see Gaudí trying things: the fascination with nature, the delight in colour, the meticulous craftsmanship, the willingness to borrow from different cultures and make something entirely new. It’s a house that wears its imagination openly, and because of that, it offers a rare glimpse of Gaudí before he became Gaudí.

Casa Vicens isn’t just a building – it’s the moment a young architect finds his voice, and Barcelona begins to change because of it.

A House With a Past

One of the things that struck me immediately about Casa Vicens is that it hasn’t always looked exactly the way it does today. The north‑east façade, in particular, tells a quiet story of how the house has changed over time – and how it has managed to keep its character despite those changes.

At the end of the 19th century, Manuel Vicens commissioned a very young Antoni Gaudí to design a summer residence. Gaudí had only just graduated, but he’d already spent years thinking about what an ideal home should be: rooted in nature, practical without being dull, and beautiful in a way that felt organic rather than ornamental. Casa Vicens was his first real chance to put those ideas into practice, and he seized it with the enthusiasm of someone who had more imagination than experience. The result was a bold, unconventional house full of ideas that were well ahead of their time.

But houses, like people, don’t stay frozen in their first moment. When the property changed hands years later and became a multi‑family home, the new owners needed more space. In 1925, the architect Joan Baptista Serra de Martínez, a friend of Gaudí’s,was brought in to extend the house. What’s remarkable is how sensitively he handled it. Painstaking effort was taken to ensure the exterior kept its original personality.

The Main Façade — Gaudí’s First Burst of Colour

One of the most surprising things about Casa Vicens is that its main façade doesn’t face the street at all, but the old garden. It’s a reminder that this was once a summer house, tucked away behind a convent wall, and Gaudí designed it with that privacy in mind. According to Joan Baptista Serra de Martínez, the architect who later extended the house, Gaudí imagined the building as if it were a kind of architectural ivy, clinging to the convent wall and growing outward from it. Once you know that, the whole composition starts to make sense.

The south‑westerly orientation wasn’t accidental either. Gaudí was already thinking like someone who understood how a house should live in its environment. By turning the façade toward the garden, he gave the rooms a gentler, more forgiving light in the heat of summer – a small but telling detail from an architect who thought of everything.

What hits you first, though, is the colour. The façade feels like an explosion — ceramic tiles, brickwork, painted wood, ironwork — all layered together in a way that must have seemed wildly unconventional in the 1880s. At the time, ceramic was mostly used indoors, but Gaudí brought it outside, letting the house shimmer in the sun like something between a Moorish palace and a botanical illustration. It was the first time he used ceramic on a façade, and it certainly wasn’t the last.

The tiles themselves reveal his early fascinations: nature, geometry, and the influence of the East. The carpentry around the doors and windows has a distinctly Japanese feel, while the inscriptions above the porch — written in old Catalan but visually reminiscent of Arabic calligraphy — speak to Gaudí’s love of cultural layering. Each inscription refers to the sun: the warmth of the home, the earliest morning light, and the cool shade of summer. Even the poetry on the walls is tied to the rhythms of nature.

Looking at this façade, you can sense a young architect testing the boundaries of what a house could be. It’s exuberant, experimental, and not yet as refined as his later works — but that’s precisely what makes it so compelling. Casa Vicens is Gaudí before the world knew his name, already dreaming in colour.

One of the things about Gaudí that people often overlook: he was thrifty. The tiles may look lavish, but there are only a handful of designs, repeated again and again. The same is true of the ironwork — the majestic entrance gate is built from a square motif used repeatedly. Even the famous trencadís mosaics that appear in his later works were, at heart, a clever way of using up broken ceramic scraps. Gaudí may have been a visionary, but he was also a man who hated waste.

A Garden That Once Flowed Into the House

The garden at Casa Vicens is much smaller today than it was in Gaudí’s time, but even in its reduced form it still feels like a little oasis tucked into the Gràcia neighbourhood. Originally, it included a waterfall and a circular fountain that cooled the porch — a kind of natural air‑conditioning long before the invention of the electric version. Gaudí designed the garden and the house as a single organism, with nature spilling into the interiors through painted ceilings, floral tiles, and leafy motifs. It’s one of the earliest examples of his belief that architecture should grow out of its surroundings rather than just sit on top of them.

The Entrance Hall — A Garden Turned Inside Out

The entrance hall of Casa Vicens feels like Gaudí’s opening statement — a small but unmistakable declaration of what he believed a home could be. Even in photographs, you can sense how deliberately he blurs the line between indoors and outdoors. The garden doesn’t stop at the threshold; it simply changes form. Leaves, flowers, and branches reappear on the walls and ceilings, as if nature has been invited inside and decided to stay.

It’s remarkable to think that Gaudí was still at the very beginning of his career when he designed this space. Yet here he is, already working with ideas that would define his later masterpieces: the celebration of nature, the careful choreography of light and colour, the belief that a house should feel alive.

The floor is one of the first clues that Gaudí was thinking far beyond the conventions of his time. It’s paved in opus tessellatum, a Roman mosaic technique that wouldn’t become fashionable again until the height of Modernisme. You see it later in his work — most notably in the crypt of the Sagrada Família — but Casa Vicens is where he first experiments with it. The effect is subtle but telling: a young architect reaching back to ancient craftsmanship to create something modern.

What I love about this room is how confidently it sets the tone for the rest of the house. It’s intimate, imaginative, and quietly radical — a space that tells you, right from the start, that Casa Vicens isn’t just a building. It’s Gaudí’s first attempt at creating a world.

The Dining Room — A Feast of Nature

The dining room at Casa Vicens is one of those spaces where Gaudí’s imagination seems to run wild in the best possible way. The room feels alive. Ivy curls up toward the ceiling, carnations bloom across the walls, birds flutter through painted foliage — it’s as if the garden has slipped indoors and decided to take over. Gaudí wasn’t simply decorating a room; he was creating an atmosphere, a world where nature is not a backdrop but a guest at the table.

This room sits at the heart of the house, and Gaudí treats it accordingly. The connection between inside and outside is deliberate and constant. The motifs echo the garden just beyond the windows, blurring the boundary between the cultivated and the imagined. It’s a reminder that for Gaudí, nature wasn’t something to imitate politely, it was something to celebrate exuberantly.

The furniture in the room is original, designed specifically for this space. Gaudí commissioned it himself, and the paintings that adorn the cabinets and panels were created by Francesc Torrescassana i Sellarés to match the room’s botanical theme. Over the decades, smoke and dust dulled their colours, giving everything a brownish cast. Thanks to careful restoration, the original tones now shine again — vivid greens, soft pinks, the warm glow of wood — revealing just how vibrant the room must have looked when it was first completed.

The Covered Porch

The covered porch at Casa Vicens is one of those spaces where you can almost feel Gaudí thinking. It has been altered over the years — at one point the original fountain was removed entirely — but thanks to a stroke of luck and the cooperation of former owners, the fountain was eventually found in the garden of a house in Girona and brought back home. Restored and returned to its original position, it now sits once again where Gaudí intended, quietly anchoring the porch with the sound of running water.

Even in photographs, the atmosphere of this space is unmistakable. You can imagine the murmur of voices, the gentle splash of the fountain, the filtered light drifting in from the garden. It must have felt like a cool, shaded retreat from the Barcelona sun.

The fountain itself is a small marvel. Its ironwork forms a kind of metallic spider’s web, delicate and geometric. When sunlight passed through it, the water droplets refracted into tiny rainbows — a quiet bit of magic created not by ornament but by physics. And the water that once flowed through it didn’t come from pipes or pumps, but from rainwater collected in deposits. Even here, in his first house, Gaudí was already thinking about sustainability long before the word existed.

The porch also reveals Gaudí’s practical side. Hidden inside the doorposts are mechanisms that were likely designed to secure the space with bars — a discreet early example of integrated security. The tilting blinds, meanwhile, regulate both light and airflow, keeping the porch and the adjoining dining room cool and comfortable.

What I find most striking is how naturally all of this fits together. The porch isn’t just an entrance; it’s a threshold between the garden and the house, between nature and architecture.

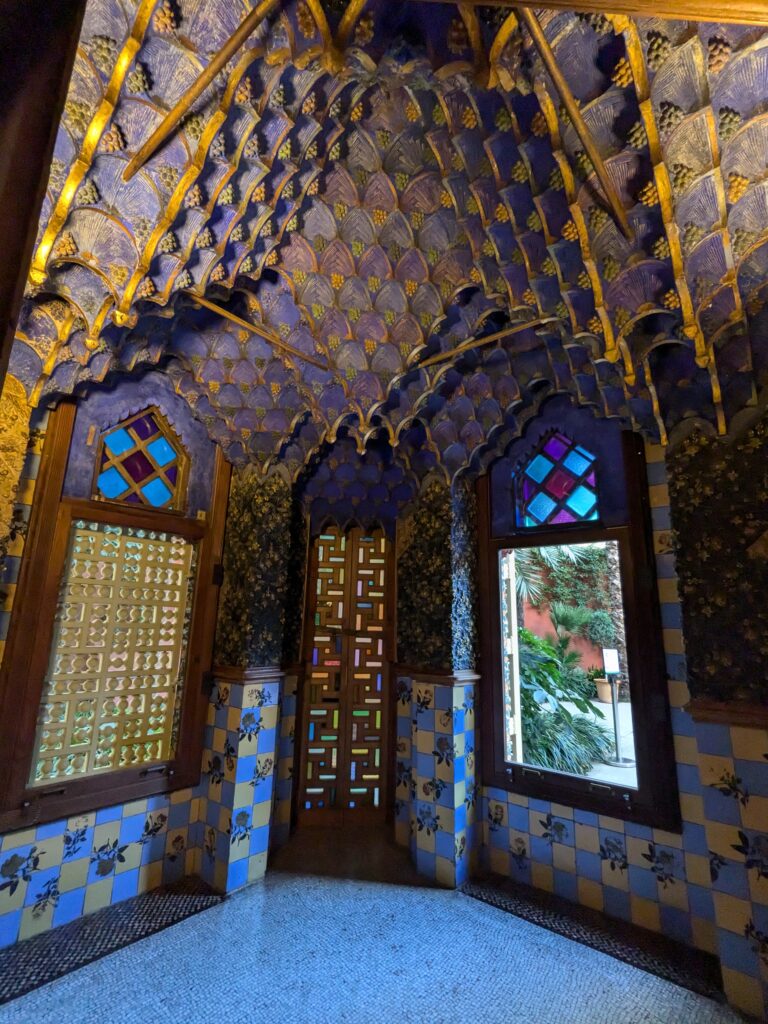

The Smoking Room — A Private Oasis of Blue and Gold

The smoking room at Casa Vicens is one of the most intriguing spaces in the house — a small, jewel‑like chamber that feels worlds away from the rest of the building. In the late 19th century, smoking rooms were a fashionable feature in bourgeois homes across Europe, a place where the men of the household would retreat after dinner to talk, smoke, and escape the formality of the dining table. It’s easy to imagine Manuel Vicens and his friends gathered here, the air thick with cigar smoke, the conversation drifting into the early hours.

What makes this room so striking is its atmosphere. Gaudí leaned heavily into Arabian influences, creating a space that feels like a tiny desert pavilion. The ceiling is painted a deep, velvety blue — the colour of a night sky — while the muqarnas, those honeycomb‑like sculptural forms borrowed from Islamic architecture, resemble palm leaves heavy with dates. Even in photographs, the room has an intimate, almost dreamlike quality, as if it were designed for storytelling as much as smoking.

The decoration is made from papier‑mâché, which sounds humble but was actually an innovative material at the time. It had only recently been patented when Casa Vicens was built and would later become popular in Modernisme interiors. Here, Gaudí uses it to create intricate reliefs that feel both delicate and exotic.

During the restoration of the house, conservators made an unexpected discovery: the gold that once covered the muqarnas wasn’t original. Beneath it lay the original blue polychrome, hidden for decades under later layers. Restoring it was painstaking work — months spent in a room barely large enough for a handful of people — but the result is remarkable. Today, the ceiling and walls reveal both histories: the restored blue that Gaudí intended, and traces of the later gold that once covered it.

What I love about this room is how unapologetically atmospheric it is. It doesn’t try to be grand or monumental. Instead, it offers a moment of escape — a private oasis where colour, pattern, and imagination take over. Even in Gaudí’s very first house, you can see his instinct for creating spaces that transport you somewhere else entirely.

The Main Bedroom — Two Worlds in One Room

The main bedroom at Casa Vicens is the largest room on the upper floor, but what makes it truly fascinating is the way it feels like two rooms folded into one. In Gaudí’s time, affluent couples often had adjoining but separate sleeping spaces, and here you can still see the traces of that arrangement. Each half of the room has its own colour palette and its own botanical motifs, almost like two personalities sharing a single space. It’s a subtle reminder of the social customs of the late 19th century, expressed not through walls but through decoration.

The ceiling continues Gaudí’s botanical theme. As in many rooms on the first and second floors, the beams are filled with ceramic coffers inspired by nature — leaves, flowers, and vines arranged in rhythmic patterns. Even in a private space like a bedroom, Gaudí couldn’t resist bringing the outdoors inside. It’s as if the garden below has climbed up the walls and settled overhead.

One of the cleverest details appears near the windows. To step out onto the outdoor area, you descend a couple of steps — a small architectural gesture with a big effect. By lowering the floor level, Gaudí was able to keep the balcony railing unusually low, ensuring that the view of the garden remains unobstructed from inside the room. It’s a perfect example of his ability to blend practicality with beauty, solving a functional problem in a way that feels almost poetic.

This bedroom may not have the flamboyance of Gaudí’s later interiors, but it has something just as compelling: a quiet, thoughtful elegance. You can see him experimenting, refining his ideas, and learning how to shape a space not just with structure, but with atmosphere. Even here, in the most private part of the house, Gaudí is already thinking like the architect he would become.

The Terrace

The terrace at Casa Vicens is another of Gaudí’s quiet masterstrokes — a space that blurs the line between indoors and outdoors, offering a moment of calm suspended between the two. It’s a place to sit, breathe, and look out over the greenery. The bench‑railing that runs around the perimeter is both practical and poetic, inviting you to linger. It’s the first time Gaudí used this architectural idea, and he liked it enough to return to it later in works like El Capricho and La Pedrera.

What’s striking is how different the view would have been when the house was first built. Today, the terrace looks out onto the compact garden and the surrounding buildings of Gràcia. But in the late 19th century, none of those neighbouring structures existed. Instead, the terrace opened onto a much larger landscape: flower beds, palm trees, palmettos, and — most impressively — a brick waterfall that acted as a natural cooling system (no longer there).

Even now, with the city built up around it, the terrace retains a sense of retreat. It’s a reminder of the house’s original spirit: a summer residence meant for rest, conversation, and the simple pleasure of looking out at nature. And like so much of Casa Vicens, it shows Gaudí experimenting with ideas that would later become signatures — the merging of indoors and outdoors, the use of natural elements to shape comfort, the belief that architecture should offer not just shelter, but serenity.

The Bathrooms

The bathrooms at Casa Vicens are a reminder that Gaudí wasn’t just an artist of colour and curves — he was also surprisingly practical. In late‑19th‑century Barcelona, most homes didn’t have running water at all, let alone a dedicated bathing area. Yet here, in his very first house, Gaudí designed a fully equipped suite divided into three distinct spaces: a bathroom, a dressing room, and a lavatory. It was quietly revolutionary, the sort of modern convenience that wouldn’t become standard for decades.

The Domed Room — A Quiet Sky Indoors

The domed room at Casa Vicens is one of those small, intimate spaces where Gaudí’s imagination feels especially tender. His passion for nature wasn’t just about borrowing motifs; he wanted nature to inhabit every corner of the house. And because Casa Vicens was designed as a summer retreat — a place for rest, leisure, and long afternoons — he created rooms that feel almost like outdoor hideaways.

This particular sitting room, perched above the smoking room, was likely intended for the women of the household. It has a softness to it, a sense of privacy and calm that contrasts with the more masculine atmosphere downstairs. The dome overhead is painted with a scene so delicate it feels almost like a window to the sky. Gaudí sketched one of the rooftop towers inside it, as if the architecture itself were drifting into view through an opening in the ceiling. Even in photographs, the illusion is convincing — you can almost imagine birds fluttering past.

The balcony adds another layer of intimacy. Its latticework filters the light and creates a gentle screen, allowing someone inside to look out without being seen. It’s easy to picture Dolors Giralt, Manuel Vicens’ wife, sitting here with a book on a warm afternoon, the sound of water from the garden drifting upward, leaves rustling in the breeze. It’s a small sanctuary, a room designed not for show but for quiet moments.

What makes this space so charming is how effortlessly Gaudí blends architecture with atmosphere. The dome, the filtered light, the suggestion of sky — it all creates a sense of retreat. Even in his earliest work, he understood that a house isn’t just a structure; it’s a place where people live, rest, and dream. And in this little domed room, you can feel that understanding taking shape.

The Blue Room — The First Appearance of a Sacred Flower

The Blue Room at Casa Vicens is one of those spaces where Gaudí’s early vocabulary begins to take shape — quietly, almost modestly, but unmistakably. The walls are adorned with a delicate botanical motif that would later become one of his recurring symbols: the passionflower, sometimes called the “flower of Christ.” It’s a plant rich in symbolism, with its intricate structure often interpreted as a representation of the Passion — the crown of thorns, the nails, the wounds. Years later, Gaudí would weave this flower into the ornamentation of the Sagrada Família, giving it a far grander stage. But here, in his first house, it appears for the very first time.

What makes this detail even more charming is its origin. The passionflower wasn’t chosen for its religious meaning alone — it was chosen because it grew right outside. Every plant depicted in Casa Vicens was found in the immediate surroundings of the house. Gaudí wasn’t importing exotic species or inventing fantastical flora; he was simply paying close attention to what nature offered him. The architecture becomes a kind of botanical diary, a record of the plants that once grew in this corner of Gràcia.

The Blue Room may be small, but it captures something essential about Gaudí’s approach: his belief that beauty begins with observation, that the extraordinary can be found in the ordinary if you look closely enough. In this quiet room, the seeds of his later masterpieces are already visible — quite literally, in the petals of a flower climbing across the walls.

The Rooftop — A First Draft of Gaudí’s Future Skylines

The rooftop of Casa Vicens is one of the clearest places where you can see the dialogue between Gaudí’s original construction and the later extension by Serra de Martínez. The area that can be walked on today belongs to the extension; the more fragile, restricted section is Gaudí’s own. Even in photographs, the contrast is visible — a reminder that this house has lived several lives.

When Manuel Vicens and Gaudí chose this site for a summer residence, the surroundings were nothing like the dense Gràcia neighbourhood we know now. The garden stretched much farther, and from the rooftop you would have seen hills, distant mountains, and perhaps even the spire of the Josepets church. The soundscape would have been different too — birds, wind, the occasional tram bell drifting across open land. It’s a small leap of imagination, but it helps you understand what Gaudí was designing for: a house immersed in nature, not hemmed in by city blocks.

The rooftop itself served a practical purpose — it collected water — but Gaudí also conceived it as a space to move through. The walkways, chimneys, tower, and stairs form a kind of circular route, an early experiment in the sculptural rooftops he would later perfect. If you’ve ever wandered across the undulating skyline of La Pedrera, you can see the lineage immediately. Casa Vicens is the prototype, the place where Gaudí first explored the idea that a rooftop could be more than a technical necessity — it could be an experience.

Casa Vicens is, in many ways, Gaudí’s manifesto house — bold, experimental, and unmistakably ahead of its time. When it was completed in 1885, Modernism was just beginning to take root in Catalonia. Gaudí was still at the start of his career, but the foundations of everything he would become are already here: the love of nature, the inventive use of materials, the fusion of beauty and practicality, and the belief that architecture should delight as much as it shelters.

Casa Vicens may not have the polish of his later masterpieces, but that’s precisely what makes it so compelling. It’s Gaudí’s first voice — youthful, daring, and full of ideas that would one day reshape Barcelona’s skyline.