Sagrada Família — A Cathedral Still Becoming

Incomplete building around the world are not rare. Maybe they ran out of money, ran out of passion or ran into unexpected roadblocks and the builders and architects move onto new projects. You see these building either in use as-is or abandoned like yesterdays trash. What’s different about the Sagrada Família is that it is still actively under construction since 1882 — under construction longer than most countries have existed. It’s an active construction site — you’ll see cranes and men in hardhats running around. The Sagrada Família is, in many ways, Barcelona’s great act of faith — not only religious faith, but faith in time, in craft, in the idea that a project can outlive its architect, its patrons, and even its century.

The first stone was laid in 1882, and since then the basilica has lived through wars, political upheavals, economic crises, and most recently, a global pandemic that halted construction for over a year. Yet it continues, slowly and stubbornly, like a living organism that refuses to stop growing. In 2010, Pope Benedict XVI consecrated it as a minor basilica, and in 2021 the Tower of Our Lady was inaugurated, crowned with a twelve‑pointed glass star that glows by day and shines like a celestial beacon by night. It’s the second‑tallest of the central towers, rising 138 metres above the floor — and it’s only a prelude to what’s coming.

The most recent milestone is the completion of the Tetramorph figures atop the towers of the Evangelists: the man or angel for Matthew, the lion for Mark, the ox for Luke, and the eagle for John. These four towers, together with the Tower of Our Lady, will form a kind of luminous halo around the future central tower dedicated to Jesus Christ — the tallest of them all, planned to reach 172.5 metres. When finished, the basilica will have 18 towers in total, each one a vertical chapter in this stone Bible.

How Gaudí Changed Everything

Gaudí joined the project in 1883, when he was just 31. At that point, only the crypt columns had been started. The commission came from the Spiritual Association of the Devotees of Saint Joseph, who probably expected a respectable neo‑Gothic church. And indeed, Gaudí began with a neo‑Gothic plan, but he just couldn’t help himself. Slowly, almost mischievously, he began introducing ideas no one had ever seen before: branching columns, hyperboloids, catenary arches, façades that looked like they had grown rather than been carved.

He worked on the basilica until his death in 1926. He knew from the beginning that he would never see it finished, but he designed it with the confidence and trusted future generations to carry the torch.

A Pyramidal Mountain of Faith

Seen from a distance, the Sagrada Família has a pyramidal silhouette, rising in tiers like a sacred mountain. Gaudí wanted the building to express the connection between the human and the divine — a kind of architectural ascent. Three sides are crowned with towers; the fourth is a semicircular apse. Each façade tells a different chapter of Christ’s life: Nativity, Passion, and Glory.

It’s often described as a “Bible in stone,” and that’s not poetic exaggeration. Every surface is carved with symbols, stories, and creatures — some familiar, some fantastical — all meant to communicate the Christian message to anyone, regardless of language or background.

To date, 13 towers have been completed:

- 4 on the Nativity Façade

- 4 on the Passion Façade

- 4 above the crossing, dedicated to the Evangelists

- 1 Tower of Our Lady

The Evangelist towers are crowned with their traditional winged symbols — lion, ox, man, eagle — rendered in gleaming sculptural form. The Tower of Our Lady, with its radiant star, is already one of the most striking features of the Barcelona skyline.

When the basilica is finished, the full set of 18 towers will include:

- 12 for the Apostles (4 on each façade; 8 already built)

- 4 for the Evangelists

- 1 for the Virgin Mary

- 1 for Jesus Christ — the tallest of all

It’s a vertical symphony, each tower a different note in Gaudí’s architectural hymn.

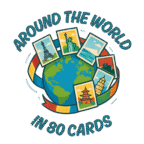

The Nativity Façade — Gaudí’s Hymn to Life

The Nativity Façade is the only one Gaudí lived to see completed, and you can feel his hand in every inch of it. It’s exuberant, overflowing, almost baroque in its joy. If the Passion Façade is bone and shadow, the Nativity is flesh and blossom.

Gaudí wanted this façade to express the joy of creation at the birth of Christ, and so he filled it with plants, animals, and scenes from daily life. It’s divided into three triangular portals, each dedicated to a member of the Holy Family:

- Portal of Hope — Saint Joseph

- Portal of Faith — the Virgin Mary

- Portal of Charity — Jesus Christ

The central portal is the tallest, drawing the eye upward to the cypress tree, symbol of eternal life. White doves perch on its branches — souls that have reached salvation.

Scenes from the Life of Christ

At the centre is the Nativity scene itself: Mary, Joseph, and the infant Jesus, flanked by the ox and the ass. To the right, shepherds gather in adoration; to the left, the three Wise Men approach with gifts. Above them, a star shines, surrounded by musical angels.

Lower down, on the left portal, Mary rides a donkey with the infant Jesus — the Flight into Egypt. On the right, Jesus as a young boy helps Joseph in the carpentry workshop.

The realism of these figures is striking. Gaudí used real people as models — neighbours, workers, even members of his own team. He made plaster casts of their faces and bodies, which were then translated into stone.

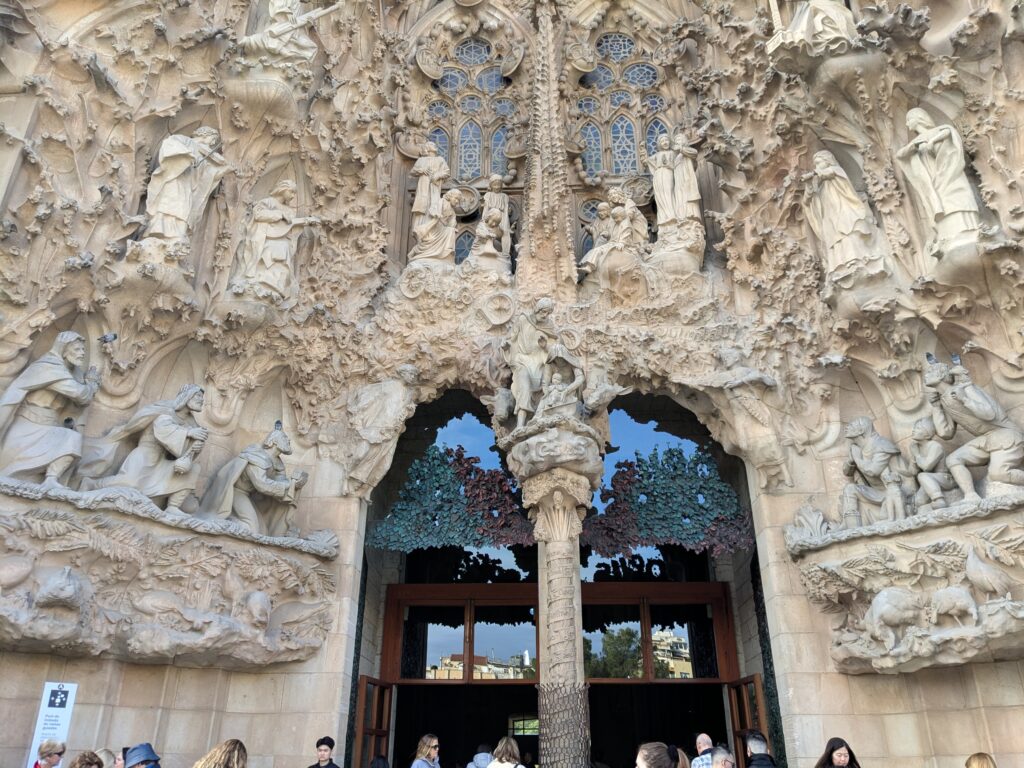

The bronze doors, installed recently, were created by Japanese sculptor Etsuro Sotoo, who has been working on the basilica since 1978. They’re covered in plant motifs — leaves, flowers, insects — as if the façade itself were alive and breathing.

The Rosary Cloister — A Quiet Corner of Devotion

Just beside the Nativity Façade is the Rosary Cloister, dedicated to the Virgin Mary. Its portal is richly decorated, echoing the style of the façade. The sculptures are by Llorenç Matamala, one of Gaudí’s closest collaborators.

At the top stands Our Lady of the Rosary, flanked by Saint Dominic and Saint Catherine, who helped spread the Rosary devotion in Europe. Below them, carved into the stone, are patriarchs and prophets — David, Solomon, Isaac, and Jacob — framed by roses.

On the left wall, a dying man is blessed by Jesus, Mary, and Joseph — the death of the righteous. On the bases of the arch, two temptations are depicted: greed, represented by a fish‑tailed figure offering coins, and violence, symbolised by a monstrous creature handing a bomb to a man. It’s a reminder that the basilica isn’t only about beauty; it’s also about moral struggle.

Inside the Sagrada Família — A Forest of Stone and Light

I’ve been in a fair number of churches over the years — Romanesque, Gothic, Baroque, the odd Victorian attempt at grandeur — but nothing prepared me for stepping inside the Sagrada Família. Most churches feel like they were built to contain something; this one feels like it’s still growing. It’s as if Gaudí didn’t design a building at all, but coaxed a forest into becoming a cathedral.

One of the first things you notice is what isn’t here. There are no side chapels lining the aisles, no rows of statues tucked into niches. Gaudí pushed almost all the storytelling to the outside façades, leaving the interior astonishingly open. The result is a space that feels less like a museum of saints and more like a living organism.

The columns don’t rise straight up like in a Gothic cathedral — they branch. Literally. Halfway to the ceiling they split and spread like the limbs of trees, supporting the vaults above with a kind of effortless grace. It’s beautiful, of course, but it’s also brilliantly practical: this branching system distributes weight so efficiently that the basilica doesn’t need the heavy buttresses and flying supports you see in medieval cathedrals.

Gaudí once said that nature was his greatest teacher, and here you can see what he meant. The geometry is complex, but the effect is simple: you feel as though you’re standing in a sacred grove.

A Temple of Light

Light is the other great protagonist of the interior. It pours in through enormous windows and skylights set into the vaults, shifting constantly as the sun moves. The stained‑glass windows are a symphony of colour: on the Nativity side, cool blues and greens that echo morning light; on the Passion side, fiery oranges and reds that feel like sunset. They were designed by the artist Joan Vila‑Grau, who followed Gaudí’s original guidelines — not to illustrate stories, but to paint the air itself.

The Crossing — Four Columns for Four Evangelists

At the centre of the basilica, the space opens into the crossing, where four enormous reddish columns rise higher and thicker than all the others. They’re made of porphyry, one of the hardest stones on earth, because one day they will support the tallest tower of the entire basilica: the tower of Jesus Christ, planned to reach 172.5 metres.

Gaudí chose that height deliberately. He believed that human work should never surpass the work of God, so he made sure the tower would be slightly shorter than Montjuïc, the nearby hill.

Look up at the capitals of these columns and you’ll see the symbols of the four Evangelists:

- the lion for Mark

- the angel for Matthew

- the bull for Luke

- the eagle for John

They stand like guardians beneath the future tower.

Beneath the crossing, set into the floor, is a mosaic with the initials of Jesus, Mary, and Joseph — a quiet reminder of the basilica’s dedication. There’s also a sculpture of Saint Joseph; facing the Passion Façade, a statue of the Virgin Mary. And above the altar hangs the crucified Christ beneath a great suspended baldachin, decorated with ears of wheat and bunches of grapes — symbols of the Eucharist.

Fifty lamps hang around it, representing the fifty days between Easter and Pentecost. It’s theatrical, yes, but also deeply symbolic — Gaudí never did anything without a reason.

The Choir Galleries

High above the aisles are tiered galleries reserved for the choir. Look closely at the railings and you’ll see small dark dots. They’re not decorative — they’re musical notes from liturgical hymns. Even the architecture sings.

The Glory Façade Doors — A Welcome in Every Language

The Glory Façade will eventually be the main entrance to the basilica, facing the sea just as Gaudí intended. The bronze doors are already finished, created by Josep Maria Subirachs. At the centre is the Lord’s Prayer in Catalan, and around it the phrase “Give us this day our daily bread” appears in fifty languages — a welcome to visitors from everywhere.

The Passion Towers — Music, Stone, and a View from the Heights

High above the Passion Façade, at the terminal of the Tower of Saint Philip, the city spreads out beneath you in a way that makes the whole basilica feel even more improbable. We were only eighty metres above the ground — not yet halfway to the height the central tower will eventually reach — but already the world below seems to shrink. From up here, the geometry of the basilica becomes clearer: the forest of columns inside, the rising tiers of towers, the sense that the whole structure is straining upward.

This is one of the four towers dedicated to the apostles on the Passion side. When the basilica is finally complete, there will be eighteen towers in total: twelve for the apostles, four for the Evangelists, one for the Virgin Mary, and the tallest of all, the Tower of Jesus Christ, rising to 172.5 metres. Gaudí loved symbolism, but he also loved hierarchy, and the towers express both.

Up close you can see the façade construction in detail. You can clearly week see shards of wine bottles and with their corks sticking out, and how Gaudí use loaves of bread and grapes as motifs for the towers.

The pinnacles at the top are covered in colourful trencadís mosaic — a technique Gaudí invented using broken tile shards. Here they depict the attributes of a bishop: mitre, crozier, and ring.

The Bell Towers — A Cathedral That Will Sing

Inside the tower, you begin to understand another of Gaudí’s obsessions: sound. The entrance‑façade towers were conceived as bell towers, not merely decorative spires. Gaudí imagined the basilica as a vast musical instrument, with the towers acting as resonating chambers. Eventually, each façade will contain 84 bells, enough to play any melody, like a stone‑built organ rising above the city.

If you look at the towers in the photos, you’ll notice the perforations. These aren’t decorative; they’re acoustic. Gaudí imagined the basilica as a kind of colossal musical instrument, with the towers acting as bell‑chambers projecting sound across the city.

The Spiral Staircase — Nature’s Geometry in Motion

The final descent is through a narrow spiral staircase, more than four hundred steps in total, the last 143 forming a perfect helix. It’s one of those moments when Gaudí’s devotion to nature becomes unmistakable. The curve of the staircase feels almost biological, like the inside of a shell or the whorl of a fern. He often said that nature was his true master, and here you can see why: the geometry is organic, efficient, and quietly beautiful.

It’s the same logic that shapes the branching columns in the nave, the hyperboloid skylights, the vaults that open like petals. Everywhere you look, the basilica seems to echo something from the natural world — not copying it, but translating it into stone.

The Passion Façade — Stone Stripped to the Bone

The sculptures on this façade are stark, angular, almost brutal. Gaudí wanted this side to feel like a skeleton — the suffering of Christ laid bare. Subirachs took that idea and pushed it further.

Starting from the bottom left, you’ll find:

- The Last Supper

- a dog, symbol of loyalty

- Judas’ kiss, the betrayal

- the flogging of Christ

- Saint Peter, distraught after denying Jesus

- Pontius Pilate, weighing his decision

In the centre, Christ carries the cross. Above Longinus on horseback, soldiers cast lots for Christ’s garments. And at the very centre of the façade is the crucifixion itself.

High above, on the bridge between the towers, a golden figure represents the resurrected Christ ascending to heaven — a note of hope amid the sorrow.

Subirachs left tributes to Gaudí throughout the façade. The soldiers’ helmets echo the chimneys of La Pedrera, and one of the Evangelists bears Gaudí’s own face. And tucked to the left of Judas’ kiss is a magic square: every row, column, and diagonal adds up to 33, the age of Christ at his death.

If the Nativity Façade is Gaudí at his most joyful, the Passion Façade is Gaudí at his most unflinching. He drew exactly what he wanted this side of the basilica to look like, and he didn’t soften a thing. His aim was to show the Passion of Christ in all its brutality — not the sentimental version, but the raw, physical suffering. Standing before it, you can see what he meant.

The great leaning columns that frame the entrance look like tensed muscles, pulled taut under strain. Above them, the next set of supports resembles ribs — a skeletal cage holding the whole façade together. Gaudí himself said this side should be “hard, bare, as if made of bones,” and that’s precisely what it feels like: a structure stripped down to its essential anatomy.

It’s impossible not to think back to the Nativity Façade at this point. The contrast is almost shocking — exuberance and abundance on one side, austerity and anguish on the other. Together they form a kind of emotional arc, the beginning and end of the story carved into stone.

A Dream Larger Than One Lifetime

Gaudí spent the last years of his life almost entirely inside the Sagrada Família — quite literally, as he moved into a small workshop on the site. He knew he would never see the basilica finished, and so he left behind an extraordinary collection of drawings, models, and instructions to guide those who would follow.

And follow they have. Since Gaudí’s death in 1926, countless architects, sculptors, engineers, and craftspeople have poured their time and talent into the project. Today, the work is led by Jordi Faulí, the current chief architect, who carries the responsibility of translating Gaudí’s vision into a 21st‑century reality.

The Sagrada Família may have begun as one man’s dream, but standing here — surrounded by the work of generations — it’s clear that it has become something much larger: a collective act of devotion, imagination, and persistence.

A Basilica Still Becoming

Stepping back outside after wandering through the Sagrada Família feels a bit like returning from another world. Most churches give you a sense of completion — even the ones that took centuries to build. This one does the opposite. It feels alive, unfinished in the most intentional way, as if it’s still stretching, still reaching, still trying to become the thing Gaudí imagined.

And perhaps that’s the point. Gaudí knew he wouldn’t live to see the basilica completed. He accepted it, even embraced it. He once said that his client — God — was in no hurry. There’s something strangely comforting about that. In an age obsessed with deadlines and efficiency, here is a building that refuses to be rushed, a project that spans generations and asks everyone who touches it to think beyond their own lifetime.

Walking around the exterior again, past the Nativity’s joyful abundance and the Passion’s stark sorrow, I found myself thinking about how rare it is to encounter a work of art that is both monumental and deeply human. The Sagrada Família is full of mathematics and symbolism, geometry and theology, but it’s also full of fingerprints — the hands of sculptors, stonemasons, glassworkers, architects, and volunteers who have kept the dream alive long after Gaudí left it in their care.

And that, I think, is what makes the basilica so moving. It isn’t just a masterpiece; it’s a collaboration across time. A reminder that some visions are too large for one lifetime, and that beauty can be built slowly, patiently, stone by stone, by people who may never see the final result but believe in it anyway.

As I walked away, the towers rising behind me like a forest of stone, I felt oddly grateful — not just for the building itself, but for the idea it represents. That imagination matters. That faith, in whatever form one holds it, can shape a city. And that sometimes the most extraordinary things are the ones still in the making.