Welcome to my new Museum With Me series. I’m kicking it off with with one of the Barcelona’s true cultural giants: the Museu Nacional d’Art de Catalunya.

Perched on Montjuïc hill inside the grand Palau Nacional, the Museu Nacional d’Art de Catalunya (MNAC) is one of those museums that quietly promises you “just a quick visit” and then steals your entire afternoon. MNAC is best known for its extraordinary Romanesque frescoes, rescued from rural churches in the Pyrenees and reassembled like time capsules. But the collection stretches far beyond that: Gothic altarpieces glowing with gold leaf, Renaissance and Baroque masterpieces by artists like Rubens, El Greco, and Ribera, and a rich selection of 19th‑ and early 20th‑century Catalan art that leads straight into modernism.

Join me as I dive into a few of my favourite works in this museum. We will see Catalan art through time, starting with the Medieval period.

Circle of the Master of Pedret — Apse of Santa Maria d’Àneu

End of the 11th – beginning of the 12th century | Fresco transferred to canvas

This monumental fresco, originally decorating the apse of Santa Maria d’Àneu in the Pyrenees, was created between the late 11th and early 12th centuries and later transferred onto canvas. Despite areas of lost paint, its imagery still reveals a rich and carefully structured religious programme.

At the top of the composition, the vault shows the Epiphany, with the Virgin Mary, the Christ Child, and the Three Magi bringing their gifts. Flanking the scene are two archangels: Gabriel on the right and Michael on the left, each holding standards and scrolls. Their presence reflects their role as intercessors for humanity on the Day of Judgment.

The upper zone also features seraphim, whose wings are covered in eyes—symbolising God’s all‑seeing knowledge. Around them appears the repeated litany “Sanctus, Sanctus, Sanctus,” echoing the chant of praise sung in Christian worship. These seraphim recall the vision described in Isaiah, where they purify the prophets Elijah and Isaiah with a burning coal. At the centre, the four wheels of Yahweh’s fiery chariot refer to the prophet Ezekiel’s vision.

Santa Maria d’Àneu was the principal church of the Àneu valley and home to an Augustinian monastic community. Stylistically, the murals are closely connected to the artistic tradition associated with the Master of Pedret, a key figure in early Catalan Romanesque painting.

Tost Baldachin — Anonymous, Catalonia (La Seu d’Urgell 1200 Workshop)

Circa 1220 | Tempera, stucco reliefs, and traces of varnished metal on wood

The Tost baldachin is the surviving central panel of what was once a complete altar canopy. In medieval Catalonia, baldachins were used to emphasise the sacred importance of the altar. While some took the form of small architectural structures, another widespread type—like this one—was the hanging baldachin. These were suspended horizontally above the altar using beams fixed into the apse walls. Only the priest celebrating Mass could see the painted surface, as its purpose was to honour and elevate the altar space rather than to be viewed by the congregation.

The imagery on the Tost baldachin echoes the themes commonly found in Romanesque apse paintings. At its centre is a majestic depiction of Christ in Majesty, rendered in vivid colours with strong black outlines. Christ holds an open book inscribed with the Latin phrase “Ego sum lux mundi”—“I am the light of the world”—a declaration frequently included in medieval representations of Christ, including the celebrated Christ of Sant Climent de Taüll.

Surrounding Christ is the tetramorph, the four symbolic creatures representing the evangelists: Matthew as an angel, John as an eagle, Luke as an ox, and Mark as a lion. Each figure fits neatly into the triangular spaces between the circular mandorla around Christ and the square frame of the panel, creating a harmonious and balanced composition typical of Romanesque design.

Master of Taüll — Paintings of Sant Climent de Taüll

Circa 1123 | Fresco transferred to canvas

One of the most celebrated works in the entire Romanesque world is the apse painting from Sant Climent de Taüll, created around 1123 and originally installed in the church consecrated that same year by Bishop Ramón de Roda of Isàvena. At its centre is the iconic image of Christ in Majesty, seated within a mandorla and raising his right hand in blessing. Resting on his knee is an open book bearing the inscription “Ego sum lux mundi”—“I am the light of the world.”

The mural depicts the Parousia, the second coming of Christ at the end of time, drawing directly from the Book of Revelation. The style is intentionally abstract and anti‑naturalistic: firm outlines, flat areas of colour, and rigid facial features give Christ a solemn, otherworldly presence. The artist’s aim was to express the supernatural nature of the scene through forms that deliberately avoid naturalism.

Surrounding Christ is a striking arrangement of the tetramorph, the four symbols of the evangelists. At the top appear the angel of St Matthew and another angel holding the eagle of St John. Below, two more angels present medallions containing the lion of St Mark and the bull of St Luke. Beneath this celestial zone, the Virgin Mary and the apostles are shown, while the triumphal arch features a circle with the hand of God and the Lamb of God with seven eyes, echoing Revelation’s imagery. On a side wall, the mural also includes the parable of Lazarus and the rich man, Epulon.

Sant Climent de Taüll is recognised internationally as one of the great masterpieces of European Romanesque art. The power of this work—created by the Master of Taüll—has resonated far beyond its medieval origins, inspiring 20th‑century avant‑garde artists such as Picasso and Francis Picabia. In 1955, a group of Catalan artists, including Antoni Tàpies, even formed the Taüll Group in homage to its enduring influence.

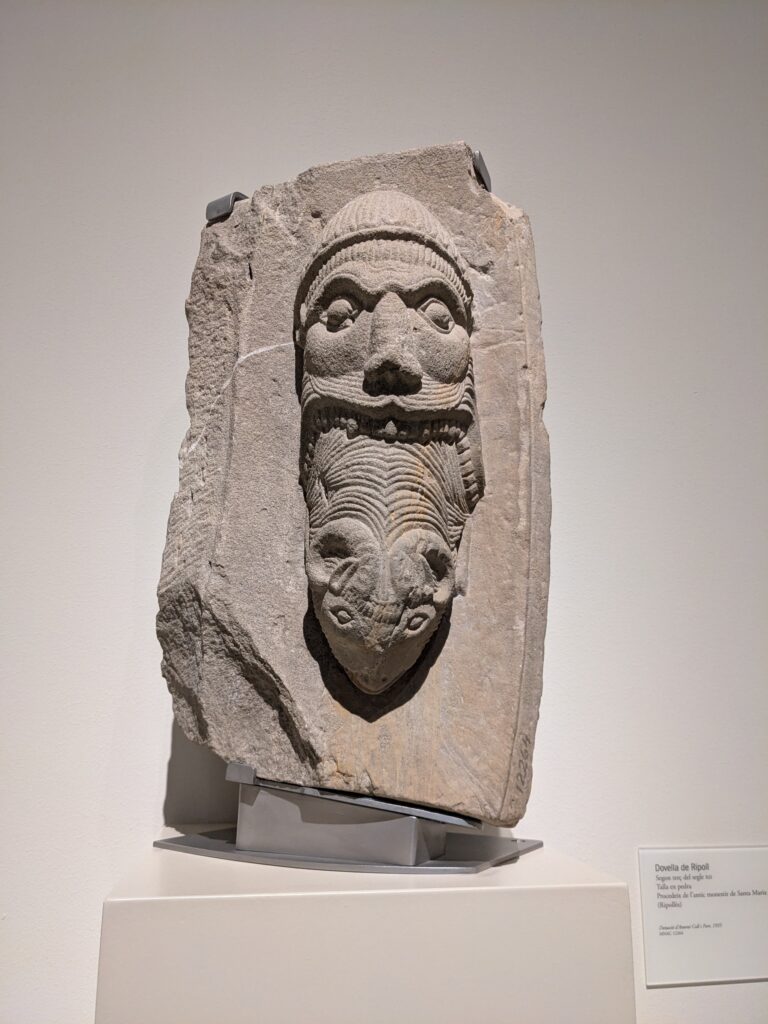

Anonymous — Voussoir from Ripoll

Second third of the 12th century | Stone carving

The monastery of Santa Maria de Ripoll was one of the major cultural and artistic centres of Europe during the Romanesque period. Although the complex originated in the 11th century, a significant phase of rebuilding took place in the mid‑12th century. This was the moment when the monastery’s celebrated sculpted doorway was created, and the works displayed here, including this voussoir and the bases of a baldachin, belong to that same period.

The baldachin bases are particularly striking. They formed the lower part of a canopy built for the high altar, likely resembling the temple‑shaped Tosses baldachin shown in the Sant Climent de Taüll room. It remains uncertain whether the Ripoll baldachin was entirely carved from stone or whether its upper structure was made of wood and then silver‑gilded.

The carved block highlighted here is a voussoir, one of the curved stones that form an arch. It features a vivid mask from whose mouth emerges an animal resembling a lamb. This piece probably came from a now‑lost doorway or window within the monastery. Although it is not part of the famous main doorway, it shares the same sculptural style – and the very same motif even appears on the great portal itself.

Anonymous — Batlló Majesty

Mid‑12th century | Wood carving with tempera polychromy

The Batlló Majesty is one of the standout treasures of the museum and a defining example of 12th‑century European wood sculpture. The term “majesty” refers to a specific type of crucifix in which Christ appears with open eyes and dressed in a long‑sleeved tunic. Rather than emphasising suffering, this form presents Christ as a serene, regal figure—an image of triumph over death and a visual announcement of the Resurrection. Its solemnity comes from its strict frontality, geometric structure, and the complete stillness of the figure.

One of the most remarkable aspects of the sculpture is its polychromy, which has survived with exceptional clarity. The tunic is richly decorated with circular and floral motifs reminiscent of luxurious Byzantine and Hispano‑Moorish textiles, which were highly prized in the medieval Christian world. Scientific studies have identified the pigments used: the red derives from cinnabar, and the blue from lapis lazuli—both costly materials. Their presence suggests the work was produced in a significant workshop, possibly near the monastery of Ripoll.

Representations of Christ as Maiestas Domini were not unique to Catalonia. A famous parallel is the Volto Santo of Lucca in Italy, venerated since the Middle Ages. Romanesque art also developed another contrasting type: the Suffering Christ, shown with a tilted head, lowered arms, and wearing only a loincloth.

Where the Majesty highlights Christ’s divine nature, the Suffering Christ focuses on his humanity, offering two complementary visions of the central figure of Christian belief.

Anonymous — Virgin from Ger

Second half of the 12th century | Wood carving with tempera polychromy and stucco reliefs

The Virgin from Ger is a fine example of Romanesque sculpture and reflects the deep tradition of Marian devotion in medieval Catalonia. Created in the latter half of the 12th century, the work presents the Virgin Mary and the Infant Jesus seated frontally in a rigid, symmetrical pose typical of the period.

The Christ Child sits on the folds of Mary’s garment, raising his right hand in blessing while holding a book in his left. This arrangement identifies Mary as the Sedes Sapientiae, the Throne of Wisdom, a symbolic seat for Christ as divine wisdom incarnate. Originally, both figures wore crowns, emphasising their royal status and recalling Christ’s lineage from King David as described in the Old Testament.

Much of the sculpture’s polychrome decoration has survived, revealing the richness of its original appearance. Areas of stucco relief—notably on the throne—add texture and depth to the carving. Together, these elements highlight the high level of craftsmanship behind this intimate yet majestic depiction of the Virgin and Child.

Master of Soriguerola — Panel of Saint Michael

End of the 13th century | Tempera and varnished metal plate on fir wood

This Panel of Saint Michael, created in a workshop active in the Cerdanya region around 1300, is considered one of the earliest surviving fragments of an altarpiece in Catalonia. While it keeps the horizontal layout typical of Romanesque altar frontals, it breaks from earlier conventions by abandoning a strict central axis, signalling the shift toward Gothic narrative style.

In Gothic art, saints were often shown as protectors and intercessors for humanity, and this panel reflects that role through a sequence of vivid scenes dedicated to St Michael. The story begins on the left, where the archangel appears in the form of a bull on Mount Gargano. A hunter shoots at the animal, but the arrow miraculously reverses course and strikes the hunter himself—an episode tied to the saint’s miraculous interventions.

To the right unfolds the Psychostasia, the weighing of souls. St Michael holds the scales while two demons attempt to snatch the soul of the deceased and drag it to hell. Below, hell is depicted in dramatic detail: Satan presides over a huge cauldron in which sinners are boiled, while devils stoke the flames beneath.

The panel’s storytelling flow and the more relaxed, less rigid treatment of the figures mark it as distinctly Gothic. Its sharply defined outlines, flat compositions, and bright, saturated colours are all characteristic of the style emerging at the end of the 13th century.

Master of the Conquest of Majorca — Mural Paintings of the Conquest of Majorca

1285–1290 | Fresco transferred to canvas

These late‑13th‑century murals are a remarkable example of medieval historical painting, illustrating the 1229 conquest of Majorca led by King James I. The scenes follow the events as recorded by contemporary Catalan chroniclers, including the Llibre dels Feits—a first‑person account by the king himself—and the Crònica by Bernat d’Esclot.

The narrative unfolds across the composition. On the right, the Battle of Portopi is shown, where Saracen forces ambush Guillem Ramon de Montcada, Viscount of Béarn. He is identifiable by his heraldic symbols: the Montcada bezants and the Béarn cows. At the centre, the artist presents a key moment—King James I’s military camp. The king stands inside his tent, surrounded by members of his retinue, each recognisable through their coats of arms. Among them is Berenguer de Palou, the Bishop of Barcelona, distinguished by his mitre in place of a helmet.

The story concludes on the left with the assault on the city of Majorca, bringing the conquest narrative to its climax.

Stylistically, these murals are a major example of early Catalan Gothic, often called linear Gothic for its strong reliance on line. Thick black outlines define the figures, the architecture, and even the distinctive rolling hills of the landscape, giving the entire work a crisp, graphic clarity that marks the transition from Romanesque to Gothic visual language.

Pere Serra — Virgin of the Angels

Circa 1385 | Tempera and gold leaf on wood

These three panels are the only surviving parts of an altarpiece once dedicated to the Virgin of the Angels. They originally came from a chapel in the ambulatory of Tortosa Cathedral and were likely created toward the end of the 14th century.

The central panel—one of the museum’s most iconic works—depicts the Virgin Mary with the Infant Jesus, who plays gently with a small bird. They are surrounded by six angels, forming a graceful and elegant composition inspired by Italian painting, a style that was highly fashionable at the time.

Displayed nearby are two related panels showing the Madonna Angelicata, one from Valencia and the other from Aragon. The remaining two panels, which depict saints, would have formed the predella, positioned on either side of the central tabernacle in the original altarpiece.

The work is attributed to Pere Serra, a major figure in Catalan painting during the second half of the 14th century.

Guerau Gener & Lluís Borrassà — Nativity, Altarpiece of the Virgin

1407–1411 | Tempera and gold leaf on wood

These panels once formed part of the main altarpiece of the monastery of Santes Creus, one of the finest examples of the International Gothic style in Catalonia. Painted between 1407 and 1411, the surviving scenes reveal the elegance, detail, and narrative richness characteristic of the period.

One panel depicts the Nativity. In the foreground, the Holy Family appears in the stable, while angels announce Christ’s birth to the shepherds in the background. A hallmark of International Gothic art—the delight in small, charming details—appears in the two pairs of angels busily repairing the roof of the manger. The scene’s gentle rhythm, balanced composition, and refined colour palette give it a distinctive sense of enchantment.

The second panel shows the Resurrection. Christ rises triumphantly from the tomb as a group of soldiers sleeps through the miracle. Their faces verge on caricature, adding a lively human touch. One guard’s axe is decorated with a small scorpion, a symbol of betrayal associated with the Jews.

The altarpiece was originally commissioned to Pere Serra, but he likely died before beginning the work. It was then taken up by Guerau Gener, who had collaborated with Marzal de Sax and Gonçal Peris in Valencia—explaining the stylistic similarities to Valencian painting of the time. After Gener’s early death, the project was completed by Lluís Borrassà, a leading figure of early Catalan International Gothic art. Born into a well‑known family of painters from Girona, Borrassà later settled in Barcelona, where he became an exceptionally prolific creator of altarpieces.

Bonanat Zaortiga — Virgin of the Mercy

1430–1440 | Tempera, stucco relief, and gold leaf on wood

This striking panel of the Virgin of the Mercy is attributed to Bonanat Zaortiga, a painter from Saragossa active during the first half of the 15th century and one of Aragon’s leading artists of the International Gothic style. His work is known for its graceful, idealised figures—elongated bodies, flowing curls, and pale, serene faces.

In this composition, the Virgin’s mantle spreads wide to shelter a diverse group of people: men and women, young and old, lay and religious. Two angels hold the mantle open as five arrows fall from the sky. These arrows symbolise the plague, one of the most feared calamities of the late Middle Ages, often interpreted as divine punishment for human sin.

The panel originally formed the central section of an altarpiece in the shrine of La Virgen de la Carrasca in Blancas, a village in the province of Teruel. The small oak tree depicted in the lower left corner refers directly to the shrine’s name—carrasca meaning “small oak.”

Gonçal Peris Sarrià — Altarpiece of Saint Barbara

Circa 1410–1425 | Tempera and gold leaf on wood

This impressive altarpiece is dedicated to Saint Barbara, who appears in the central panel holding two of her traditional attributes: a tower, recalling her imprisonment, and a palm leaf, symbolising her martyrdom. As was typical in altarpieces of the period, a Calvary scene is placed above her, while the side panels narrate key episodes from her life.

Saint Barbara was widely invoked for protection against lightning and storms, which explains her strong following in rural communities such as Puertomingalvo, the Aragonese town near the Valencian border where this work originally stood. Many altarpieces destined for southern Teruel were commissioned from Valencian workshops, which played a major role in shaping Gothic art in the region.

The Valencian Gothic School developed between the 14th and 15th centuries under the influence of two foreign masters: Gherardo Starnina, who introduced Florentine artistic traditions, and Marzal de Sax, a Flemish or German painter who brought northern European elements. The artist attributed to this altarpiece, Gonçal Peris Sarrià, represents the fusion of these two currents into a distinctly Valencian style. His work is marked by expressive, picturesque details and a strong emphasis on colour.

Lluís Dalmau — Virgin of the ‘Consellers’

1443–1445 | Oil on oak wood

With the Virgin of the Consellers, the Valencian painter Lluís Dalmau—active in Valencia and Barcelona between 1428 and 1461 and working under King Alfons the Magnanimous—introduced the technical and stylistic innovations of Flemish painting into Catalan Gothic art. The panel is remarkable not only for its vivid colours and meticulous detail, but also for the striking realism in the portraits of the five consellers (councillors) of Barcelona’s Town Hall, who appear as donors.

The work was commissioned to decorate a newly renovated chapel on the ground floor of what is now the Ajuntament (Town Hall) building. Because it is one of the best‑documented works of Catalan Gothic, we know that the painting also served a political purpose: the municipal authorities sought to impress both citizens and visitors by hiring a prestigious artist and insisting on the finest materials—such as high‑quality Flemish oak, explicitly required in the contract signed on 29 October 1443. It was a lavish commission.

A new realism

The councillors instructed Dalmau to portray them exactly as they appeared in real life, without idealisation: “according to the proportions and habitudes of their bodies, with the faces as true as they are in real life.” This commitment to realism was groundbreaking in Catalonia.

The painting also adopts another Flemish innovation: the breaking of hierarchical perspective. Traditionally, religious figures were shown larger than laypeople, but here the councillors—kneeling respectfully before the Virgin and Child—are the same size as the holy figures. The divine and the human share the same visual space, signalling a shift in artistic and cultural attitudes in the mid‑15th century.

Jaume Huguet — Altarpiece of Saint Augustine

Circa 1463–1470/1475 | Tempera, stucco reliefs, and gold leaf on wood

The Altarpiece of Saint Augustine was commissioned in 1463 by Barcelona’s tanners’ guild (blanquers) for the high altar of the church of Sant Agustí Vell. Its sheer scale—this is the largest Gothic altarpiece ever produced in Catalonia—combined with the economic crisis affecting the region from the mid‑15th century meant that the project stretched on for more than twenty years before reaching completion.

Because of its size and the long period of execution, much of the demanding painting work fell to Huguet’s workshop assistants and collaborators. Of the eight surviving panels, five are now displayed at the Museu Nacional d’Art de Catalunya. Only two panels—the Last Supper and the Consecration of Saint Augustine—are attributed entirely to Jaume Huguet himself.

For the remaining panels, Huguet likely provided the overall design and composition, but the painting is thought to have been carried out by a leading member of his workshop, probably from the Vergós family, who were closely associated with Huguet’s studio. The stylistic differences are easy to spot: the expressive, characterful faces of the Apostles at the Last Supper and the figures surrounding Saint Augustine contrast noticeably with the more restrained faces on the other three panels displayed to the left.

Ayne Bru — Martyrdom of Saint Cucuphas

1502–1507 | Oil on wood

This dramatic panel shows the martyrdom of Saint Cucuphas and is displayed alongside a companion painting of Saint Candidus, depicted as a knight. Remarkably, these two works are the only surviving paintings by Ayne Bru, an itinerant Flemish artist.

The scene is striking for its intense realism. The executioner’s fierce, hardened expression contrasts sharply with the saint, who collapses in a faint, appearing to accept his death with calm resignation. Bru’s technical skill is matched by the intellectual depth of the composition: to the right, a group of richly dressed figures stand absorbed in what seems to be a theological discussion, entirely unmoved by the violence unfolding before them.

Originally, the panel formed part of the main altarpiece of the monastery of Sant Cugat del Vallès, and it is considered one of the most significant Catalan artworks of the Renaissance period. As a charming historical detail, the painting arrived at the museum in 1907 in an open‑top car owned by the painter Ramon Casas—a vehicle that now appears in the museum’s Modern Art collection.

Master of Frankfurt — Triptych of the Baptism of Christ

1500–1520 | Oil and gold leaf on wood

This elegant triptych—a three‑panel artwork with hinged wings—centres on the Baptism of Christ, shown on the main panel. The side panels expand the narrative: on the left, the Archangel Michael weighs a soul, while on the right, St Francis of Assisi receives the stigmata.

When the wings are closed, the outer faces reveal another scene entirely: the Annunciation, with the Archangel Gabriel and the Virgin Mary painted in grisaille, a monochrome technique that imitates sculpture. The patron’s banner also appears on the exterior panels.

The triptych originally came from a church in Segovia and is attributed to an anonymous Flemish painter, known as the Master of Frankfurt after two of his works preserved in that city.

Giovanni Antonio Canal (Canaletto) — Return of Il Bucintoro on Ascension Day

1745–1750 | Oil on canvas

In this lively Venetian scene, Canaletto captures the celebratory atmosphere of the harbour of San Marco on Ascension Day. Each year, the Doge—the elected leader of the Venetian Republic—was ceremonially taken out into the bay aboard the state barge, the Bucintoro, to give thanks for Venice’s victory over Dalmatian pirates. The painting shows the richly decorated vessel, marked by its red banner and forty oars, being brought back to shore and surrounded by a flotilla of smaller boats.

Canaletto was renowned for his meticulously detailed views of Venice, and this work showcases the city’s most iconic landmarks: the Doge’s Palace, the Biblioteca Marciana, and the Campanile rising behind them. On the far left, the domes of Santa Maria della Salute appear in the distance, completing this vivid portrait of Venice at its most festive.

Peter Paul Rubens — Virgin and Child with Saint Elizabeth and the Young Saint John

Circa 1618 | Oil on canvas

This painting depicts the meeting of the family of Saint John the Baptist with the family of Christ, who were related according to Christian tradition. Rubens drew inspiration from Renaissance Florentine painting, where the Holy Children were often shown nude in religious scenes. The result is entirely characteristic of Rubens’ style: strong, energetic figures rendered with a sense of vitality and physical presence.

Several versions and copies of this composition exist, but this example is considered one of the finest. Rubens painted it while on a diplomatic mission to the Court of Mantua, a period during which his extensive travels exposed him to a wide range of artistic traditions. This work reflects how those encounters enriched his visual language, adding new influences to his already expansive iconography.

Peter Paul Rubens — Virgin and Child with Saint Elizabeth and the Young Saint John

Circa 1618 | Oil on canvas

In this warm and intimate scene, Rubens brings together the family of Saint John the Baptist and the family of Christ, who were related according to Christian tradition. His inspiration came from Renaissance Florence, where artists often portrayed the Holy Children nude, lending the figures a sense of innocence and naturalism. Rubens transforms this idea into something distinctly his own, filling the composition with the robust, energetic forms that define his style.

Multiple versions of this composition are known, but this one is considered among the finest. Rubens painted it while serving on a diplomatic mission to the Court of Mantua, a period when his constant travel exposed him to a wide range of artistic influences. The painting reflects how these encounters broadened his visual vocabulary, enriching his already diverse iconography.

El Greco (Domenikos Theotokopoulos) — Christ Carrying the Cross

1590–1595 | Oil on canvas

In this moving image, Christ carries the cross not as a sign of impending martyrdom but as a symbol of victory over death. His expression is serene, marked not by suffering but by calm trust in eternal life. Paintings like this were created for devotional use, encouraging viewers to reflect on Christ’s example and aspire to spiritual improvement.

The work is a quintessential demonstration of El Greco’s technique. He shapes the figure with dramatic contrasts of light and shadow, creating a powerful sense of volume. The composition glows with bright, expressive colours and subtle, varied brushstrokes, all of which reflect the influence of his formative years in Italy. Although El Greco painted several versions of this theme, this canvas is considered one of the most representative of his distinctive, deeply personal style.

Giambattista Tiepolo and Workshop — Christ on the Way to Golgotha

After 1738 | Oil on canvas

This painting depicts Christ carrying the Cross on the road to Golgotha, the site of the Crucifixion. The scene is marked by a strong sense of theatricality, conveyed through the expressive gestures and dynamic poses of the figures, as well as the layered arrangement of the composition.

Colour plays a central role: Tiepolo uses tone and contrast to create striking illusionistic effects, a hallmark of his style and a reflection of his celebrated mastery of fresco painting, the medium that made him famous.

The canvas is an exact, smaller‑scale copy of Tiepolo’s own version of the subject in the church of Sant’Alvise in Venice, his native city. He revisited this theme multiple times, producing several variations.

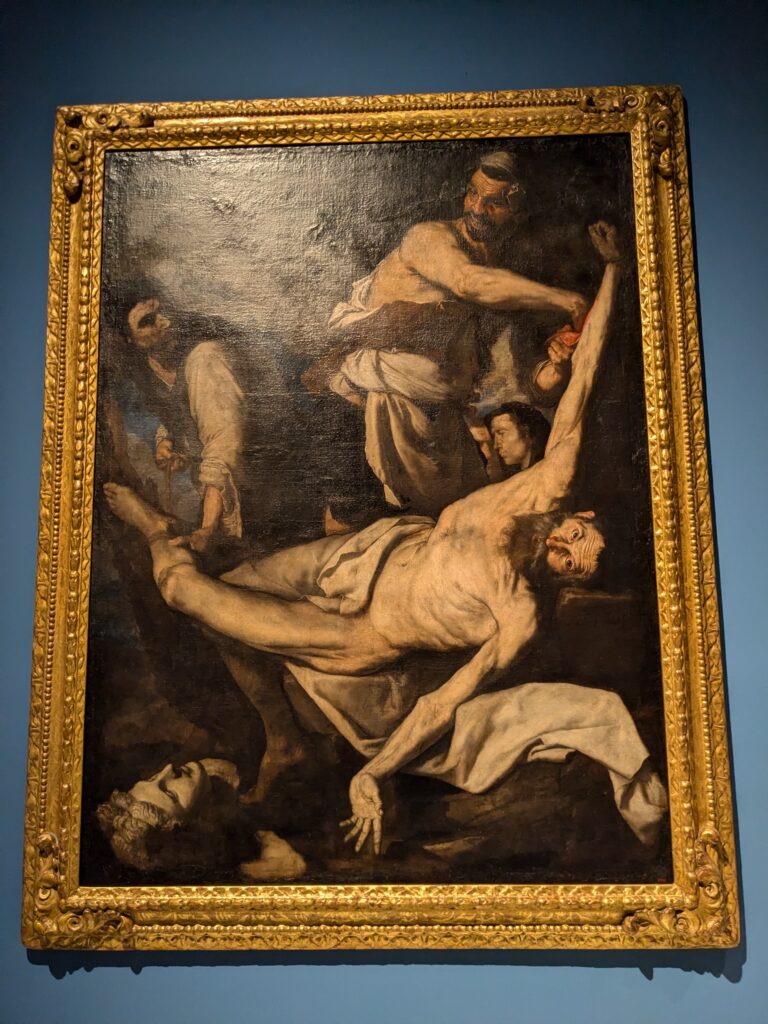

Jusepe de Ribera (“Lo Spagnoletto”) — Martyrdom of Saint Bartholomew

1644 | Oil on canvas

This powerful painting depicts the martyrdom of the Apostle Bartholomew and is considered one of Ribera’s finest works. It reveals the artist’s uncompromising commitment to extreme realism in religious subjects. Bartholomew, nearly naked, looks out toward the viewer in helpless resignation, while his executioner—drunken and brutal—flays him with chilling delight.

At the saint’s feet lies the head of a Classical sculpture, representing the god Baldach, and in the background two hooded priests observe the torture. The painting likely originated in the Charterhouse of Jerez before entering the collection of King Louis‑Philippe of France, where it was displayed for a decade in the Louvre Museum. It later belonged to the Art Nouveau artist Alexandre de Riquer, who eventually sold it to the Museums Committee, allowing it to enter the National Museum.

Ribera’s signature and the date are inscribed on the stone beneath the saint’s head, anchoring this dramatic and deeply human scene in the artist’s own hand.

Francisco de Zurbarán — Saint Francis of Assisi according to Pope Nicholas V’s Vision

Circa 1640 | Oil on canvas

This sombre and atmospheric painting is based on a 15th‑century legend in which Pope Nicholas V envisioned the uncorrupted body of Saint Francis of Assisi. Zurbarán heightens the mystical quality of the scene by setting the figure against a deep, dark background and illuminating him with a single dramatic light source. The effect gives the saint a sculptural presence and emphasises the geometric simplicity of his habit.

The stark lighting and enveloping darkness create a sense of mystery that evokes the supernatural nature of the Pope’s vision, blurring the boundary between the real world and the painted one. Although several versions of this subject exist, some attributed to Zurbarán himself and others to his workshop, this canvas, along with two related works in Lyon and Boston, is considered among the finest examples of the artist’s treatment of the theme.

Jean‑Honoré Fragonard — Portrait of Charles‑Michel‑Ange Challe

Circa 1769 | Oil on canvas

This lively portrait shows a gentleman seated casually on the edge of a fountain while his horse drinks beside him. He wears clothing “in the Spanish style,” a deliberately old‑fashioned and picturesque costume that, in the cultural language of the time, carried a playful, ironic tone.

Recent discoveries of related Fragonard sketches have linked the painting to his celebrated Fantasy Figures series and suggest that the sitter is likely Charles‑Michel‑Ange Challe, an architect. The work showcases Fragonard’s unmistakable virtuosity: swift, energetic brushstrokes, richly textured paint, and shimmering colour effects that give the portrait its vibrant, animated presence.

Juan de Roelas — The Adoration of Christ

1600–1610 | Oil on canvas

In this ambitious composition, Juan de Roelas brings together the sacred and the earthly, portraying with striking precision the family of the Marquis and Marchioness of Ayala alongside the biblical Adoration of the Christ Child. The painting is deliberately divided in its treatment: the foreground, where the Ayala family appears, is rendered with meticulous detail and a clear Flemish influence, while the background, containing the religious scene and landscape, is painted with a looser, more fluid brushwork reminiscent of Italian Mannerism.

A portrait of rising status

Beyond its devotional subject, the painting also celebrates a moment of social elevation. Antonio Francisco de Fonseca y Toledo, Lord of Coca, had recently been granted the title of first Marquis of Ayala. Living in Valladolid, he commissioned this work to include himself, his wife Mariana Tavera de Ulloa, and their young children, Antonio and María de Fonseca. The family appears as direct witnesses to the holy scene, and the Marquis shows no hesitation in placing himself on the same visual level as the sacred figures – a confident assertion of his new status.

Francisco de Goya — Manuel Quijano

1815 | Oil on canvas

Goya painted this portrait in 1815, shortly after the end of the Napoleonic Wars. By then he was already completely deaf, yet he continued attending performances directed by his close friend Manuel Quijano, a composer and theatre director who had long been an influential figure in Madrid’s musical and theatrical life. Though little‑known today, Quijano was once celebrated for his work in the tonadilla, a popular musical genre enjoyed both by the lower classes and by the court. When the tonadilla fell out of fashion, he turned to adapting opera scores, and from 1837 onward he served on the Madrid Theatres Committee, which selected works for performance on the city’s stages.

A portrait born of friendship

Unlike Goya’s formal commissions, this portrait was created out of friendship, painted with loose, spontaneous brushstrokes that convey immediacy and trust. Goya almost certainly gave it to Quijano as a personal gift. The artist strips away unnecessary detail—he even omits the sitter’s arms—so that all attention falls on Quijano’s introspective, dreamy face. With his tousled hair and sensitive expression, Goya presents him as the very image of a Romantic artist.

Titian (Tiziano Vecellio) and Workshop — Girl Before the Mirror

After 1515 | Oil on canvas

Girl Before the Mirror has long invited multiple interpretations. Some scholars view it as a kind of vanitas allegory, with Beauty personified as a young woman gazing into a mirror and lamenting the fleeting nature of physical perfection—an erotic image carrying a moralising message. Others trace the subject to a Petrarchan sonnet, in which a lover envies the girl’s mirror because it reflects the face he adores, creating a subtle love triangle between woman, lover, and mirror.

This painting is a replica produced in Titian’s workshop, based on an original dated 1515 and now in the Louvre. Its existence—and the popularity of the theme—reflects the Humanist culture of the early 16th century, when such poetic, layered subjects were in high demand.

A Glimpse Behind the Curtain: Modern Art in the Making

Before leaving the museum, I wandered into the modern‑art wing. There’s a space where they’re putting together new pieces. The space was in that wonderful in‑between state where nothing is quite ready, but everything is full of promise. Crates were open, monumental pieces were being hoisted into place, and the whole room had the energy of a stage just before the curtain rises.

There’s something strangely intimate about seeing artworks before they’re officially unveiled. You catch them in their rawest moment, surrounded by ladders, bubble wrap, and the quiet concentration of the people installing them. It’s a reminder that museums aren’t static temples; they’re living organisms, constantly shifting, preparing, reinventing themselves.

Even half‑assembled, the modern‑art area already felt bold and full of personality – a sharp, exhilarating contrast to the medieval altarpieces and Renaissance saints I’d just spent the afternoon with. If the old masters whisper, these pieces look ready to shout.

I can’t wait to see the space once everything is in place. But honestly, there was something special about catching it mid‑transformation, like being let in on a secret before the rest of the world arrives.

Nightfall Over Barcelona

Stepping out of the museum, I found myself suddenly in the open air again, the city already wrapped in night. Barcelona has a particular way of glowing after dark – not loudly, but with a kind of quiet confidence. The domes, rooftops, and distant hills settle into silhouette, while the streets below pulse with that unmistakable Catalan rhythm: unhurried, warm, alive.

After spending hours with saints, martyrs, and Venetian barges, the view felt like a gentle return to the present. The city lights shimmered against the sky, and for a moment it was as if the whole place were exhaling.

Read more about the pieces in the Museum’s Catalogue: https://www.museunacional.cat/en/catalogue